For nearly 40 years, a controversial California law has required companies to place warning labels on their products alerting consumers to the potential health threats posed by chemicals, or else face lawsuits from lawyers, private citizens and advocacy groups.

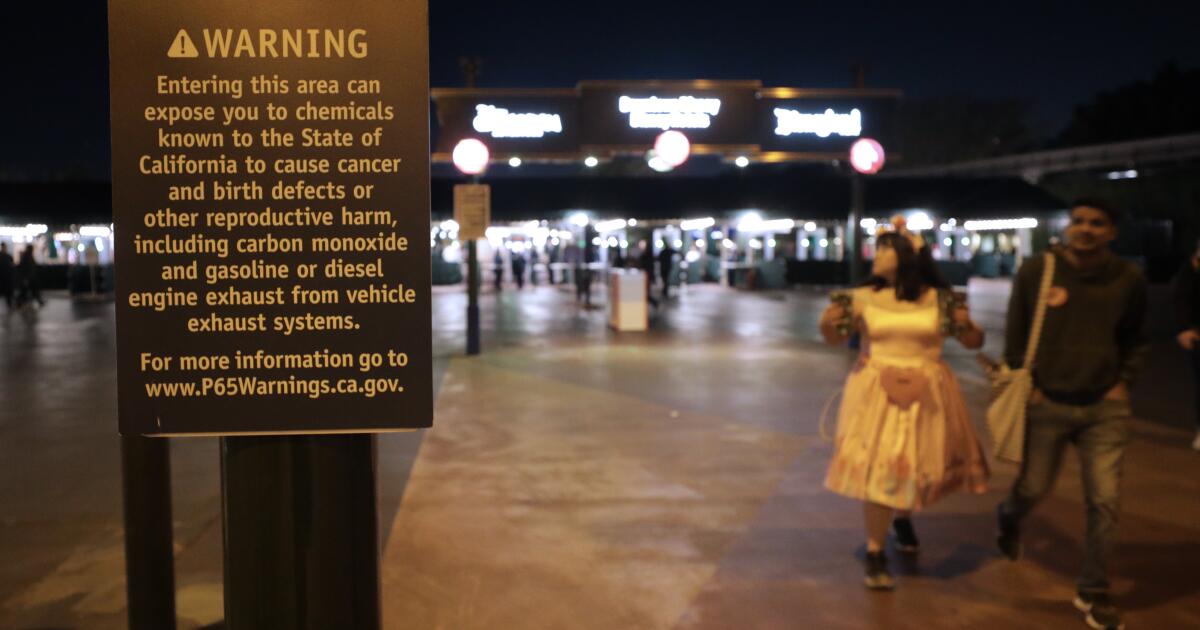

Passed as a ballot initiative, the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986 has resulted in warnings being affixed to everything from vinyl-covered Bibles to gas station pumps, advising that exposure to some 900 chemicals can cause cancer, birth defects or reproductive harm.

Ever since the passage of Proposition 65, policymakers and business groups have argued over whether the law is effective in preventing people from ingesting and inhaling toxic chemicals, or just providing a payday to plaintiffs attorneys.

Now, a new study published in Environmental Health Perspectives has concluded that Proposition 65 has curbed exposure to toxic substances in California — and nationally.

“If you live in California, the warnings are everywhere,” said Kristin Knox, a senior researcher at the Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit that investigates the links between breast cancer and chemicals found in consumer products and the environment.

“They’re on all sorts of stuff. So it’s very easy for people to make fun of Prop. 65 because you’re like, there’s warnings on my coffee and in my parking garage. But, for us, that made it even more important to be able to go and see if it’s having effects.”

The study, conducted by Silent Spring and UC Berkeley researchers, suggests the law helped to reduce exposure to toxic substances commonly found in diesel exhaust and plastic materials.

In order to gauge the law’s effectiveness, study authors examined the prevalence of chemicals found in blood and urine samples collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The researchers analyzed concentrations of 11 chemicals placed on the Proposition 65 warning list and monitored by the CDC between 1999 and 2016. They included several types of phthalates, chemicals used to make plastics flexible; chloroform, a toxic byproduct from disinfecting water with chlorine; and toluene, a hazardous substance found in vehicle exhaust.

They found that the majority of samples had significantly lower concentrations of these chemicals after their listing. But the levels didn’t just decline in California, they fell nationwide.

However, California residents had lower chemical levels compared to the rest of the U.S., possibly due to more stringent environmental regulations and consumer awareness, according to researchers.

Study authors surmised that the concentrations fell, in part, because businesses removed the chemicals from their goods to avoid warning labels.

“It sounds like they reformulate to avoid having to put a Prop. 65 label on their product,” Knox said. “But when they reformulate, they reformulate nationwide. It’s not like they’re going to make a product just for California. And so this state regulation is actually having a national impact.”

But swapping one chemical for an unlisted substitute has sometimes resulted in its own consequences.

“That’s not what we want to see, and that’s an argument for regulating chemicals as a class, rather than specific chemicals,” Knox said.

Business leaders have long been skeptical of Proposition 65’s effectiveness. They argue that the extensive list of chemicals has led to nearly universal warnings, which they say has undermined the law’s original intent and given consumers warning fatigue.

Since 2010, companies have settled more than $200 million in Proposition 65-related lawsuits, according to the California Chamber of Commerce. Proposition 65, they say, has resulted in a cottage industry of so-called bounty hunters that target California companies for payouts.

“Prop. 65 is infamous for its ubiquitous warnings and its bounty hunters who have abused the law to shake down businesses,” Adam Regele, vice president of advocacy for CalChamber, said in a statement.

“For many chemicals, it requires warnings at levels 1,000 times below the level known to cause no effect in animal studies. It therefore should come as no surprise that listing a chemical under Prop. 65 prompts businesses to avoid it — if they can. The more important question is whether these changes have any public health benefit, and particularly at what cost to consumers.”

Experts say some of the legal action is warranted and paved the way for reform.

Dr. Meg Schwarzman, a physician and environmental scientist at UC Berkeley, said Proposition 65 has encouraged regulation that has reduced air pollution. Diesel was recognized as a carcinogen and listed under Proposition 65 in 1990.

Several lawsuits were lodged against businesses, including school bus manufacturers and a major grocery chain. Perhaps the most notable was filed by then California Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris, who sued tenants at the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach for failure to warn residents that diesel emissions can cause cancer.

Not long after its Proposition 65 designation, the California Air Resources Board classified diesel exhaust as a toxic air contaminant, enabling the agency to regulate it. It later adopted a number of rules curtailing diesel pollution in heavy-duty trucks and equipment at ports.

From 1990 to 2014, diesel emissions dropped by 78% in California, compared with 51% nationally.

“Californians have lower body burdens of many known toxic chemicals than people living outside of here,” said Schwarzman. “And that shows that whatever combination of our environmental laws targeting toxics is having an effect.”